You’ll see the sentiment expressed in many of our AI Week articles, in other content at DMN, and even in AI-forward books like What To Do When Machines Do Everything.

The human touch will still be needed. For marketing; for business in general.

And that’s correct. There’s no doing without humans, not just for the immediate future, but possibly not at all. It’s easy to agree with that, but in fact there’s a very specific reason machines can’t do what humans can do, and it’s worth exploring what it is.

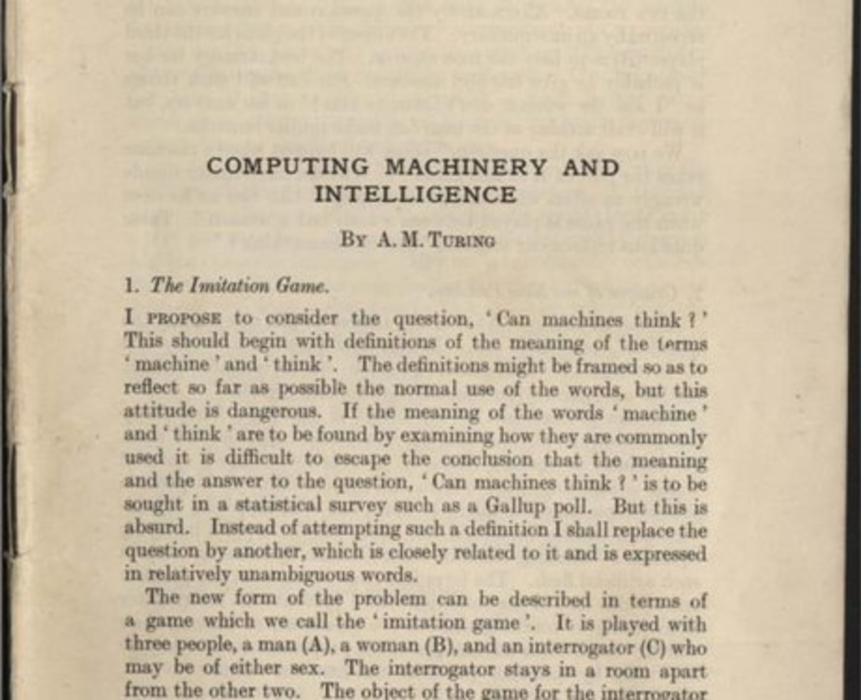

It all goes back to Turing

Alan Turing was the towering genius of computer science; he was less adept at philosophy, even though his famous 1950 paper, “Computing Machinery and Intelligence,” was published in a leading philosophical journal, Mind. If you’re familiar with the “imitation game,” now better known as the Turing Test, skip the next paragraph. I’ll see you further down the page.

Turing claimed that intelligence could reasonably be ascribed to any machine which could pass the following test. The machine and a human being, hidden behind a screen, provide answers to questions put by another human being who doesn’t know if h/she is addressing a person or a robot. If the questioner can’t distinguish the machine from the human, then the machine can be credited with (artificial) intelligence. As many have pointed out, having a human and a robot providing competing answers is unnecessary. A simpler version of the test would just put a robot behind the screen, and certify it as smart as soon as it was able to fool people.

The test, however, obscures a deeper philosophical problem, and one which holds the key to the question whether machines can ever be called “intelligent,” in the human sense, at all. Take away the screen. Sit face to face with another human being; pose questions; listen to the answers; and ask yourself, “Why do I unhesitatingly ascribe intelligence to the human being?” In other words, it’s the age-old problem of whether other minds exist, or whether the people we deal with every day are, in effect, flesh-and-blood machines, quite unconsciously producing intelligible speech and behavior.

We can’t address the problem of whether machines can be intelligent unless we first have a good idea of why we ascribe intelligence to our fellow citizens. When we do.

Syntax and semantics (don’t panic)

The easiest approach to that question is via two relatively technical terms, syntax and semantics. It’s easy to imagine machines — in fact, thanks to natural language generation (NLG) models, they (imperfectly) exist — that generate grammatically correct answers to questions. And they could be programmed to produce answers which are not only linguistically impeccable, but also true: super chatbots. A machine with capabilities, hooked up to the right weather service, could unerringly answer questions like “Is it still snowing?” That’s the syntax part: Having a machine speak a language, speak it well, and utter truths in that language.

But nobody suspects the weather chatbot of looking out the window, seeing cold white stuff, and making an inference from its experience. Nor (normally) does anyone suspect the weather bot of meaning that it’s snowing rather than raining. That’s the semantic part. Most of the time, humans not only speak a language intelligibly, and utter truths in that language, but what we say reflects beliefs we have, based on our previous and current experiences.

Can machines mean?

The philosopher Donald Davidson has a very neat summary of what we generally expect to be the case when we attribute meaning (semantic content) to what someone says:

“What is needed is evidence that the object [the thing speaking, be it human or robot] uses its words to refer to things in the world, that its predicates are true of things in the world, that it knows the truth conditions of its sentences. Evidence for this can come only from further knowledge of the nature of the object, knowledge of how some of its verbal responses are keyed to events in and aspects of the world…The easiest way to make this information available is to allow the interrorgators to watch the object interact with the world.” — Davidson, “Turing’s Test,” in Problems of Rationality (2004)

Put simply, we ascribe intelligence to our fellow human beings, not because they can produce syntactically impeccable (often true) sentences, but because we observe what happens in their lives (and ours) to make that possible. We go outdoors, we look at things, we develop beliefs about them, and each of those beliefs is part of an enormously complex network of other beliefs (snow falls from the sky, the sky is above us, falling is due to gravity) — which are, for the most part, consciously held. If you prefer your philosophy with a continental flavor, the German writer Heidgger said that we have “being-in-the-world” — a concerned, stakeholder relationship with our environment.

Some will say that a sufficiently complex machine just will make the jump from syntax to semantics. It will, indeed, start consciously observing the world, and drawing inferences from what it observes. After all, what are humans but very complex machines?

Of course, trying to explain what humans do by attributing something like a “soul” or a “conscious self” to each of us doesn’t really explain anything. But the assumption that complexity will inevitably lead to semantic capability (consciousness, if you prefer) is no less of a speculative leap. Maybe it will; but right now, neuroscience, for all its sophisticated tracking of neural activity, has no idea how or why such activity converts into lived, conscious experience.

Until we have some basis for the expectation that machines will make the leap from syntax to semantics, we have no basis for any expectation that they will be able to make, on our behalf. the creative, concerned, outcome-directed decisions which govern our lives and our work. Oh sure, they’ll be able to imitate us, doubtless with greater and greater sophistication.

But they won’t be like us. Not until they can be like “themselves.”