With The Players’ Tribune, Derek Jeter wants to turn athletes into journalists, and I say it’s about time. Forget that the ones who did graduate college had a co-ed named Zelda write all their English papers for them. Forget the players—like Jeter—who warmed to the press as if they were tax collectors and so are bursting with decades worth of great material. I’ll even forgive the fact that most of them make more money in a month than I’ve amassed in a 40-year career in journalism.

Back in the Sixties, guys like Tom Wolfe and Hunter S. Thompson ushered in “New Journalism”—the idea being that a writer who inserted himself or herself into the story could provide compelling inside details. George Plimpton, a journalist, made a career of posing as an actual athlete to break down the walls of the professional sports world. Now we have Plimpton-in-reverse, athletes pretending to be writers. I think that could be much more interesting—if editors with J-school degrees don’t get in the way, that is.

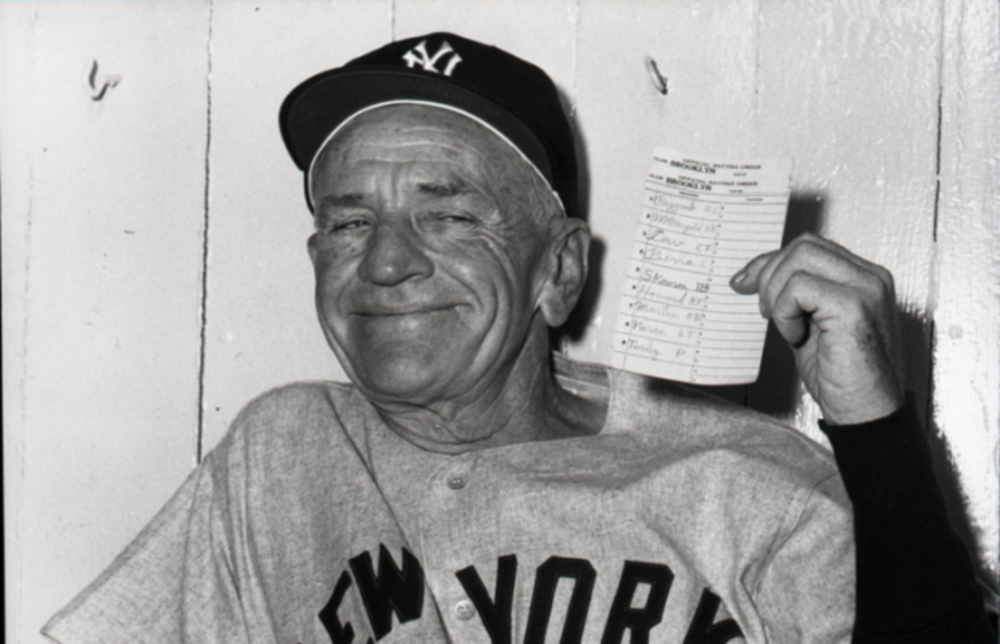

Locker rooms have a long and great tradition of wordsmithing. “There comes a time in every man’s life, and I’ve had plenty of them,” once stated Casey Stengel (above), baseball’s answer to Will Rodgers. And long after Yogi Berra’s three MVP awards and 13 World Series titles fade from memory, gems such as “It ain’t over till it’s over,” and “It’s like déjà vu all over again” will reside in the vernacular alongside quotes from Shakespeare.

In a letter on the home page of The Players’ Tribune, which debuted online last week, Jeter writes that he is “in the process of building a place where athletes have the tools they need to share what they really think and feel. We want to have a way to connect directly with our fans, with no filter.” From your mouth to John Peter Zenger’s ears, Derek. Then maybe the Tribune will treat us to one-of-a-kind observations like those below. Pro athletes, you see—highly developed personalities not limited by the strictures of writing instructors and grammarians—can often turn a phrase like a well-oiled double play:

“I’ve won at every level, except college and pro.” –Shaquille O’Neal

“If you ever dream of beating me, you’d better wake up and apologize.” –Muhammad Ali

“Ball handling and dribbling are my strongest weaknesses.” –David Thompson

“They shouldn’t throw at me. I’m the father of five or six kids.” –Tito Fuentes

“I wouldn’t ever go out to hurt anybody deliberately, unless it was, you know, like a league game or something.” –Dick Butkus

And the quote that should grace the masthead of The Player’s Tribune, from the incomparable Dennis Rodman: “If you have a problem with my answer that’s your problem, not my problem.”

It’s only fair that I warn the budding Berras and Alis about the dangers of truth-telling. Some people may not like it, and you’d better be prepared for that. (Take heed, you growing movement of pro athletes making promising New Journalistic sorties into the criminal justice system.) Author of the pioneering player diary Ball Four, Jim Bouton, wound up on the New York Times bestseller list and baseball’s black list. He was called a traitor, never invited back to old timers’ games, and insists that his cousin, a solid college pitching prospect, was dismissed by the major leagues because his name was Bouton.

“I believe the overreaction to Ball Four boiled down to this: People simply were not used to reading the truth about professional sports,” Bouton said.

But I am Derek, am I ever. You’re in our game now, kid, so don’t play it safe. Bring the cheese. Remember what Yogi said: “If you don’t know where you are going, you might wind up someplace else.”

Note: Dismissive statements made above on the general merits of editors do not apply, of course, to my own editor-in-chief, Ginger Conlon.